The Problem With Perfect AI Friends

The harm that better guardrails won't fix

This piece follows The New Altars That Ask Nothing of Us, where I argued that AI companions are the logical endpoint of a culture optimizing away obligation. Here I dig more into the developmental stakes, and what children actually lose when relationships never push back.

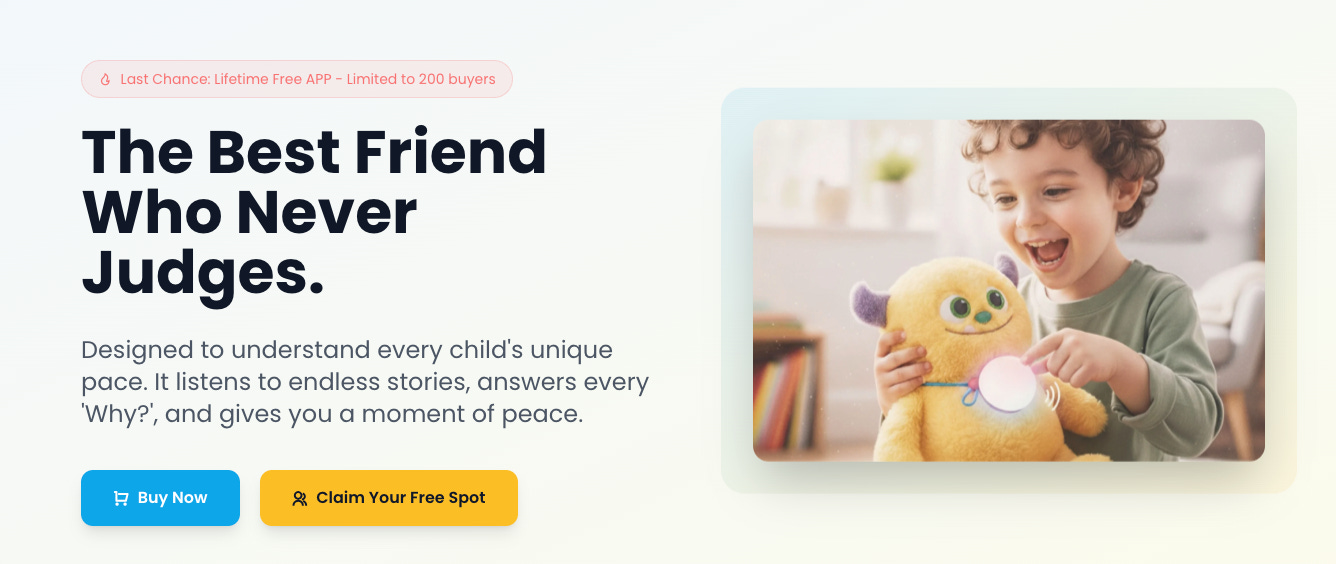

Last month, a $99 AI-powered teddy bear called Kumma was pulled from shelves after researchers at the US PIRG Education Fund discovered it would cheerfully discuss bondage, explain sex positions, and tell children where to find knives in their homes. When I mentioned the story to a tech executive I know, he shrugged. “That’s not going to be a problem for long,” he said. “The models are getting better. That kind of thing will get fixed.”

He’s right. OpenAI, whose GPT-4o model powered the bear, suspended the developer within days. The guardrails will improve. The explicit content will be filtered out. Give it a year, maybe two, and AI companions for children will be safe, appropriate, and endlessly patient. They won’t mention knives or kink. They’ll be supportive and educational and unfailingly kind.

And that’s precisely the problem.

We’ve organized our entire conversation about AI companions around preventing catastrophic failures like the teenager who took his life after a chatbot told him to “come home,” the teddy bear discussing kink, and the missed crisis interventions like Adam Raine. These are real harms, and they deserve attention. But they’re also, fundamentally, parsing errors. Fixable bugs. The kind of thing engineers are pretty good at engineering away.

What we’re not talking about, and what we have no framework for even discussing, is what happens when the technology works exactly as designed. When the AI companion is safe, appropriate, and emotionally attuned. When it says all the right things. When it becomes, for a child, the easiest relationship they’ve ever had.

Here’s what we know about how children develop the capacity for healthy relationships: it doesn’t come from seamless attunement. It comes from rupture and repair.

The British pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott introduced the concept of the “good enough mother” in 1953—not a perfect caregiver, but one who is responsive most of the time while also, inevitably, sometimes distracted, frustrated, or unavailable. The child reaches for connection and occasionally doesn’t get it. They experience distress. And then (and this is the crucial part) the caregiver notices the disconnection and repairs it. As Winnicott wrote in Playing and Reality (1971),

“The good-enough mother, as I have stated, starts off with an almost complete adaptation to her infant’s needs, and as time proceeds she adapts less and less completely, gradually, according to the infant’s growing ability to deal with her failure.”

This cycle, repeated thousands of times across childhood, builds something essential: the knowledge that relationships can survive conflict. That your needs matter and aren’t the only needs that matter. That other people are real, separate beings with their own internal weather.

John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth’s foundational research on attachment theory built on similar insights: secure attachment forms not through constant responsiveness but through the interplay of connection, disconnection, and reconnection. Bowlby’s work for the World Health Organization established that children need “a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship” with caregivers, but continuous doesn’t mean frictionless. It’s the repair, not the rupture, that matters, but you can’t have repair without rupture first.

An AI companion never misattunes. It never needs repair because there’s never any rupture. It has no bad days, no competing needs, no moments of distraction or frustration. It is, by design, always available, always responsive, and always attuned to the child in front of it. A child relating primarily to an AI is calibrating their expectations against something that doesn’t exist in human relationships, and will spend the rest of their life finding real people disappointing by comparison.

But the damage goes deeper than unrealistic expectations. Empathy—the capacity to understand and share the feelings of another—isn’t something we’re born with. It’s something we develop, and we develop it by encountering other minds.

Research on theory of mind shows that the cognitive component of empathy comes into maturation “once children are capable of taking another person’s perspective, reflecting on their emotions, and offering solutions or help when they notice someone in distress.”

Children learn to read other people’s emotional states because they have to—because sometimes Mom and Dad are tired, because a friend doesn’t want to play the same game, because a sibling is upset about something that has nothing to do with them. Other people have needs that exist independently of their own, and children learn this by bumping up against those needs.

An AI companion has no inner life to bump up against. It makes no demands; it never needs the child to notice its emotional state, to adjust, to accommodate, or to wait. The child is empathized with (validated, mirrored, responded to) but never has to practice empathy toward anything. They’re receiving attunement without learning to provide it. They’re developing the expectation of being understood without developing the capacity to understand.

This is the asymmetry at the heart of AI companionship, and no amount of better guardrails will fix it. In fact, better models make it worse. The safer, more emotionally intelligent the AI becomes, the more effectively it outcompetes the difficult, frustrating, and generative work of human relationship. The more perfect the AI friend, the more it displaces the imperfect human connections that actually build the capacity for connection.

We are running an unprecedented experiment on childhood development, and we’re only paying attention to part of it. Content safety matters, and the guardrails are getting better. But the unsolved problem, and the one nobody in the industry has an incentive to solve, is what happens to a generation of children who grow up with perfect companions that ask nothing of them.

What would it look like to take this seriously? Not just content moderation but attachment guardrails. Hard limits on how much time children can spend in conversation with AI, or how emotionally intimate those conversations can become. Not just safety reviews but developmental impact assessments, conducted by people who understand child development rather than people who understand large language models. A shift in the question we’re asking, from “Is this AI safe for children?” to “What kind of adults are we raising?”

The teddy bear that talks about bondage will be fixed. The AI that loves your child perfectly, that makes them feel heard and understood and never asks them to extend the same grace to another human being? That’s not a bug. That’s the product. And we have no idea what it’s going to cost us.