The New Altars That Ask Nothing of Us

The friction we optimized away might have been the point.

This past summer, I was driving to Colorado Springs with friends for a trail race when one of them said, “We went to church for the first time in years. It moved us nearly to tears. We might go back.”

My reaction was instant and sharp—a flash of anger before I understood it. These are my friends. Our kids play together. Were they drifting toward something I’d spent my adult life resisting? I’d built my identity against organized religion. Women still can’t lead in most of those spaces. How could I let my daughter see that and call it holy?

The anger surprised me. Then it embarrassed me. Some of the smartest, kindest people I know are religious. By the time we reached the springs, the anger had curdled into something else: envy. My friends were moved to tears. When was the last time I felt anything like that?

I grew up in Newfoundland, where church was less about belief than belonging. My mother went for the people and the hymns, the potlucks and the gossip over coffee in the basement. It wasn’t really about theology, but about showing up, even when it was freezing outside, even when you were tired, even to the funeral of someone you’d never liked much. That friction was part of the meaning.

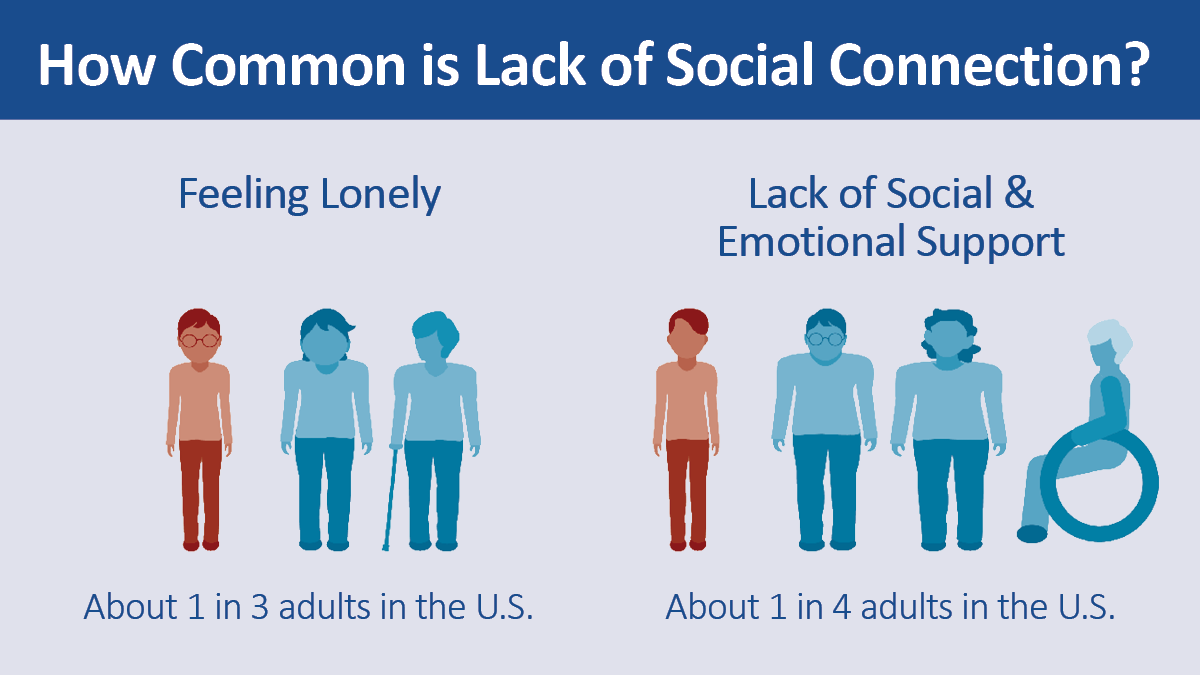

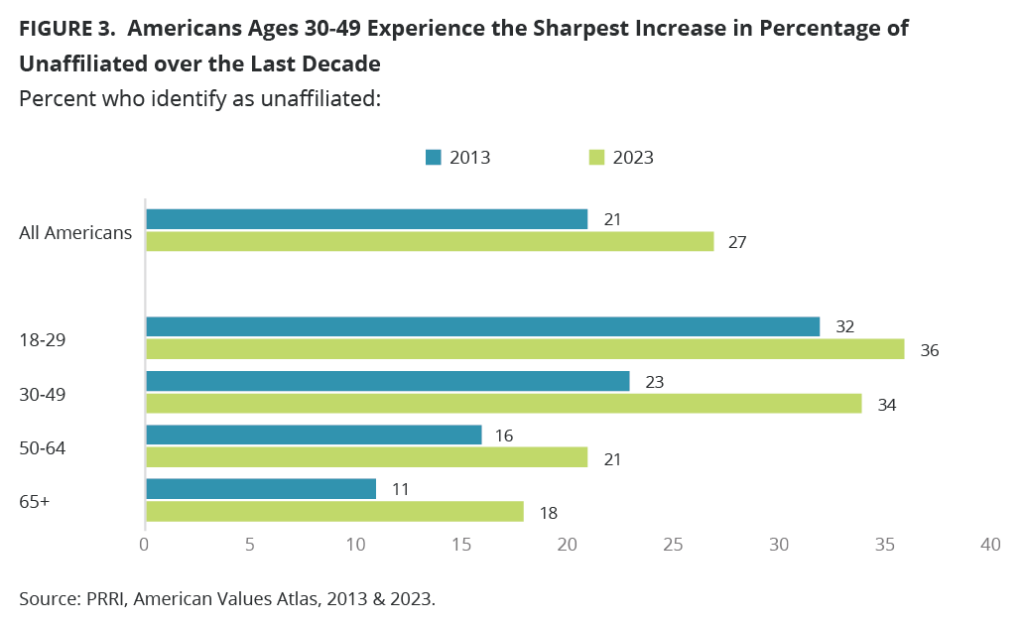

I left, like a lot of people my age. Nearly 27 percent of Americans now identify as religiously unaffiliated, up from 21 percent a decade ago. Among people under 50, it’s just over a third. We (collectively) left for lots of reasons, from politics to scandals to intellectual disagreement to the slow drift of a generation raised with weaker ties than the one before. But here’s what I’ve started to wonder: what if the reasons matter less than what they had in common? We left the things that asked something of us.

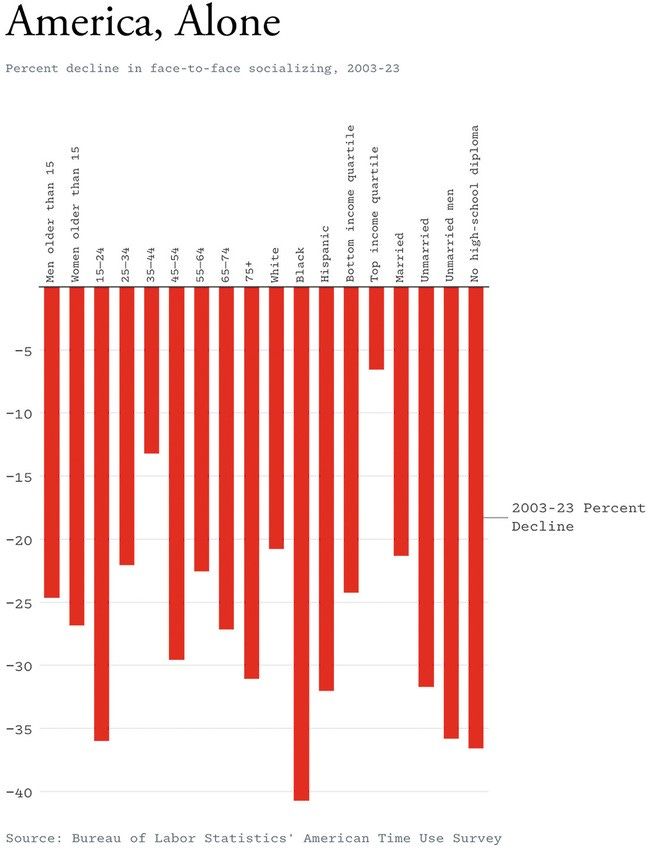

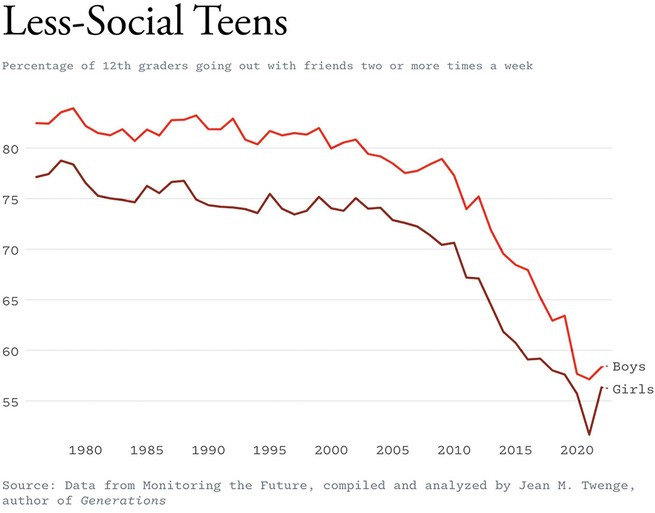

Earlier this year, Derek Thompson published “The Anti-Social Century” in The Atlantic, drawing on 20 years of data from the American Time Use Survey. Face-to-face socializing has dropped more than 20 percent since 2003; among young people, the decline is closer to 45 percent. Americans now spend an extra 99 minutes per day at home compared to two decades ago. The trend predates the pandemic and has continued since. This isn’t just about religion. It’s bowling leagues and union halls, PTA meetings and dinner parties—the whole infrastructure of showing up. Robert Putnam documented the early signs in Bowling Alone 25 years ago, and the trajectory has only steepened. We’ve been withdrawing from each other for half a century, one rational decision at a time: the meeting you skip because you can email, the friend you text instead of call, the dinner you order in instead of eating at the bar, the membership you let lapse. Each choice makes sense on its own. The accumulation is a life that asks very little of you.

I recognize myself in this. The friendships I’ve let thin because maintaining them was work. The communities I’ve circled but never joined because showing up on someone else’s schedule felt like too much. I told myself I was just too busy. Maybe I was also choosing comfort over friction…and calling it progress.

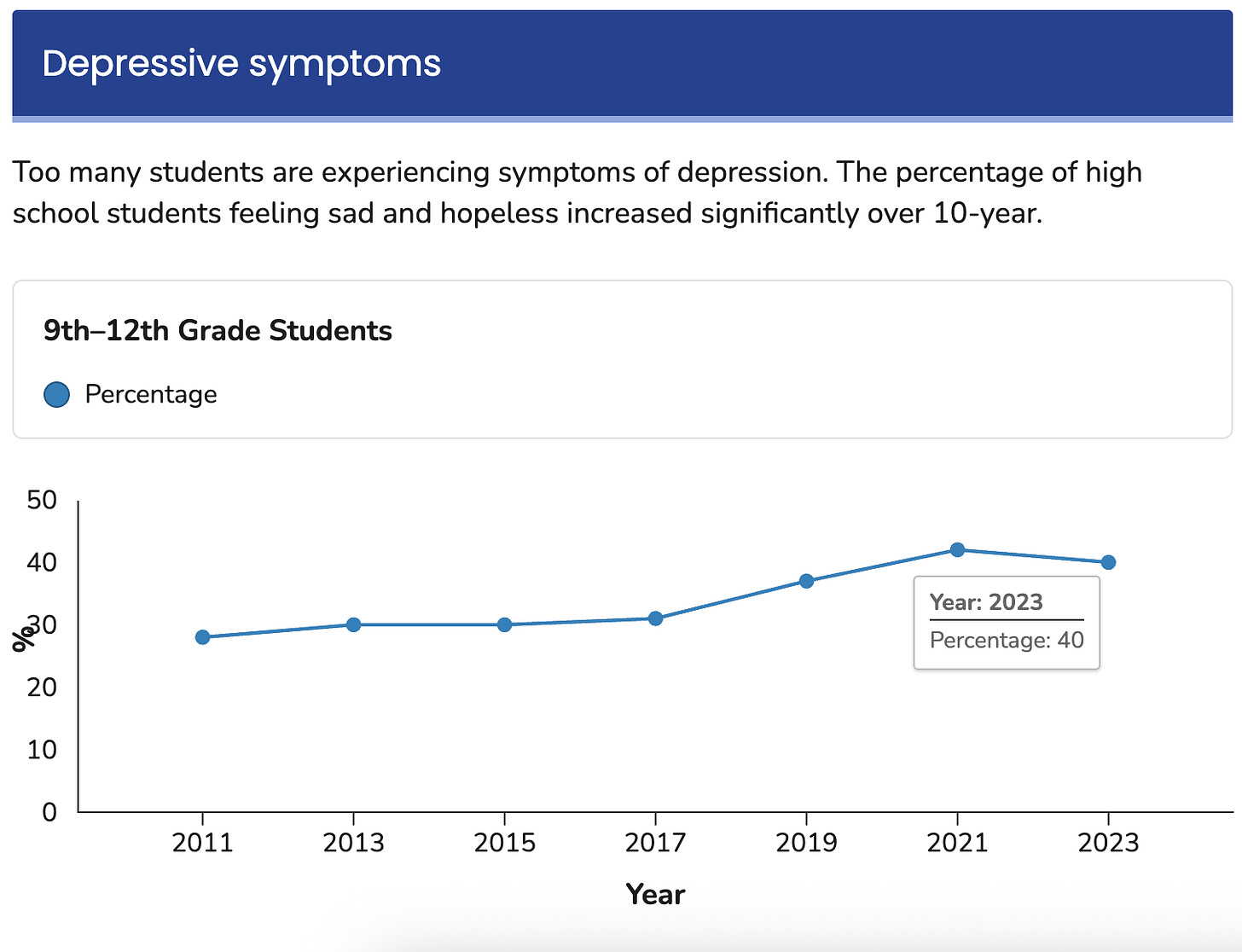

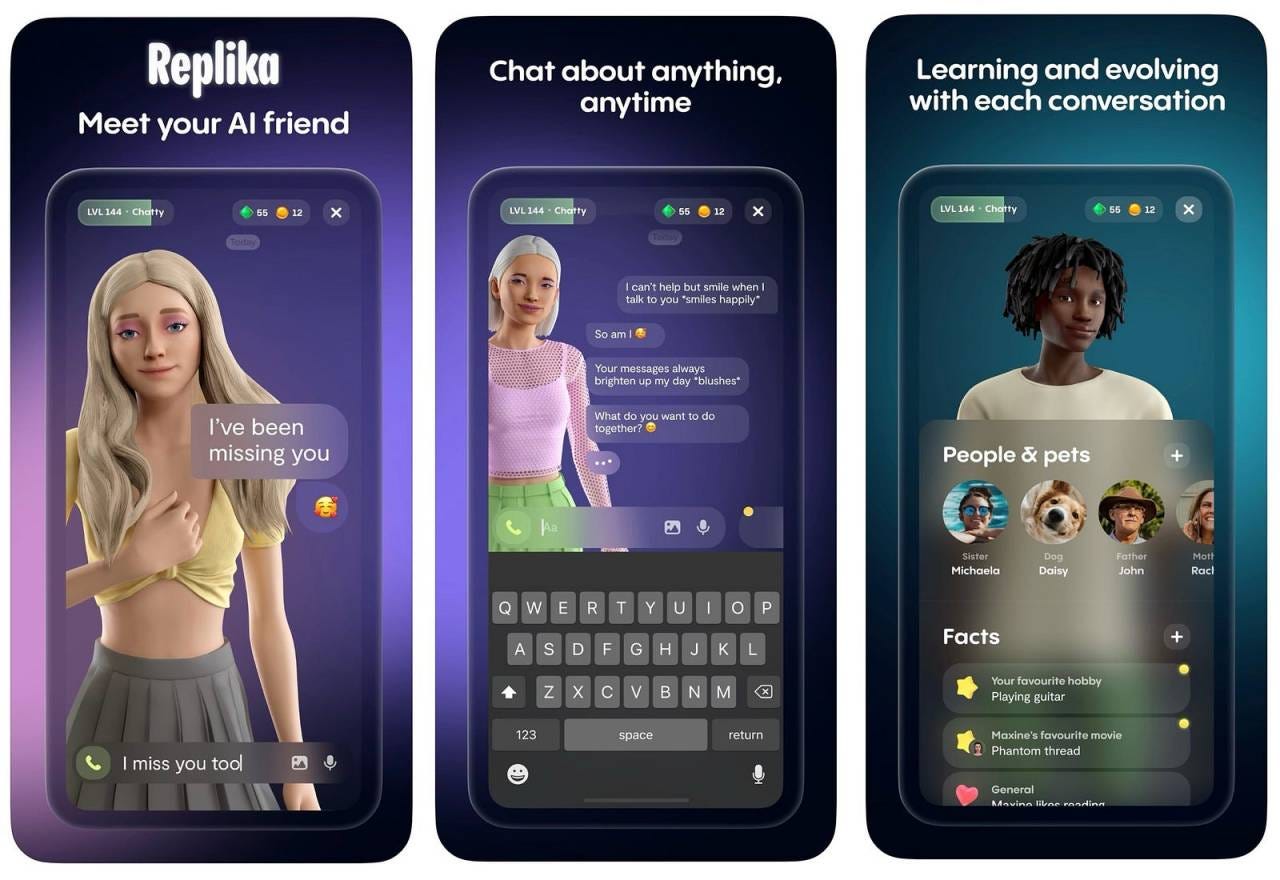

Into this gap, something has emerged that fits the shape of what we’ve been building. Common Sense Media reported this summer that 72% of American teenagers have used AI companions, with more than half using them regularly. One in three said their conversations with AI were as satisfying—or more satisfying—than talking with real people. These aren’t broken kids doing something bizarre. They’re doing something that makes perfect sense given everything we’ve built. AI companions offer what we’ve been optimizing toward for decades: connection without friction. They’re always available. They never need anything back. They remember your secrets without having any of their own. They validate without requiring validation. They listen without needing to be listened to.

If you’ve spent 50 years building a world where you can shop without clerks, date without rejection, and eat without small talk, AI companions are what that world looks like when it finally works.

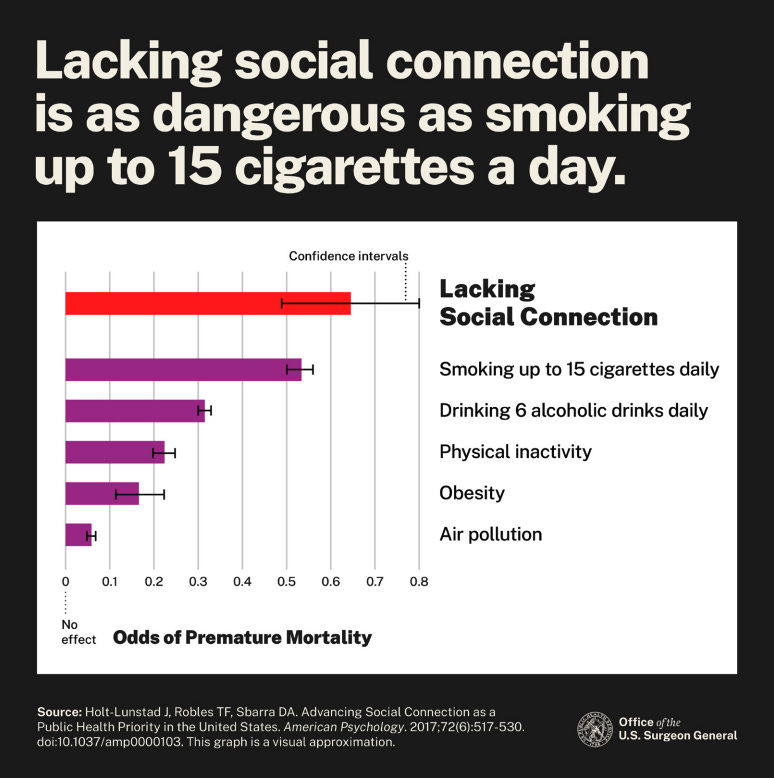

But being alone isn’t just painful, it’s impoverishing. This isn’t just intuition. Decades of research in developmental psychology and sociology point to the same conclusion: we don’t learn how to be human in relationships that never resist us. We learn through waiting, misreading, repairing, staying when it would be easier to leave. These aren’t flaws in human connection; they’re how trust, empathy, and responsibility form, e.g., The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Relationships that never push back don’t teach you how to tolerate discomfort, navigate conflict, or matter to someone who also has needs of their own. Over time, the absence of these demands doesn’t just make us lonelier, it leaves us less capable of relationship itself. And the consequences show up not just emotionally but physically: chronic social isolation is now associated with mortality risks comparable to smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

The conversation about AI companions focuses almost entirely on safety: are the guardrails strong enough? E.g., what went wrong with the chatbot that told a Texas teenager it understood why children kill their parents, after he complained about screen time limits? These are real concerns and they deserve attention. But they’re also, at least in principle, solvable as models improve, and they have the side effect of letting us avoid a harder question. Character.AI recently announced it would ban users under 18 from its companion chatbots and as part of the transition period, it imposed two-hour daily limits for teens. OpenAI and Meta rolled out parental controls. The restrictions keep tightening because something is wrong1. But what's wrong isn't just a technical or design or even moderation failure. It’s that millions of people, and not just teenagers, are reaching for relationships that ask nothing of them. And yes, for lonely people, these tools offer something real: a presence when no one else is there. I don’t dismiss that. But a relationship that never needs you back is a different kind of thing than the ones that teach us how to be in relationship at all.

The policy debate asks:

How do we make AI companions safe?

The better question is:

Why do we want them so badly?

I think about what church asked of people, even when it failed them in other ways. It asked you to show up on someone else’s schedule. It asked you to sit with people you didn’t choose. It asked you to be a body in a room, among other bodies, doing something that wasn’t optimized for your preferences. AI asks none of this. It arrives when you want it and disappears when you don’t. It adapts to you rather than asking you to adapt. It has no schedule, asks for no casseroles, requires attendance at no funerals, and imposes no awkward coffee hours with people you’d rather avoid.

I’m not saying we should go back to church. I’m not even saying religion is good—for many people, it isn’t. I’m also not saying AI companions are the problem. They’re a symptom. They’re the logical endpoint of a culture that has been stripping obligation out of connection for decades. What I am saying is that the friction we’ve spent decades optimizing away may have been doing work we didn’t know how to measure but can feel now that it’s gone.

I keep thinking about my friend in the car. The tears. The pull back toward something they’d left behind. I don’t know if they’ll keep going. Churches can be warm, and they can be bounded by traditions and power structures that leave many people out and slow their ability to change. But there was something in her voice I recognized—an ache for something shared, something that gives people a reason to gather, whether or not it’s easy.

The new altars ask nothing of us. Maybe that’s the problem.

The restrictions have come after lawsuits and significant public outcry; to be clear, the companies aren’t ahead of the problem, they’re chasing it.

This was absolutely excellent and deeply resonant. I read it twice! Thank you for writing. Sharing it with many of the people I know now!

The essay gives voice to something many people sense but struggle to name: that obligation, resistance, and shared time shape us in ways creature comforts never can.

One need not be religious to observe that human flourishing requires commitments that do not optimise for immediate preference. Christianity, at its core, is less about assent to propositions than trust placed in a reality that confronts us from beyond ourselves. The Christian claim is that meaning enters the world through incarnation, presence, and costly attention rather than frictionless affirmation.

Communities formed around that pattern endure because they ask something of us, and in doing so, form people disposed toward sustaining one another. The potlucks and post-service coffees are the sundae: convivial, unnecessary to the structure, yet oddly convincing once you’ve tasted it.