Who Do You Turn To?

A small experiment in asking each other first.

A few months ago, I’m walking through Boulder trying to find a cafe I’ve never been to. Google Maps is doing that thing where it can’t quite tell which way you’re facing until you start moving, so I’m standing there awkwardly turning in a slow circle. An older woman nearby notices and asks where I’m headed.

“Neptune Café,” I say.

“Oh sure,” she begins, “go past the sandwich shop, then take a left at the bike shop, you’ll see a mural on the corner…”

She’s kind, patient, and generous with her details. And I’m smiling and nodding, pretending to follow, already half-tuned out. The moment she’s out of sight, I glance down at my phone and let the arrow guide me instead.

I think about that moment a lot. She reminds me of people who still know where they are in the world—people who learned to navigate without an app. She also reminds me of a friend I met in grad school. I’ll call him Jay.

Jay is a fantastic orienteer. He learned the skill through years of practice in the backcountry and had an intuitive sense of direction. When we’d wander downtown San Francisco or road-trip across the country, he always seemed to know exactly where we were and where we were going. It was charming, and sometimes helpful, but I had Google Maps. As long as we had signal, I felt just as capable.

Jay, though, often wanted to travel by map. I mean an actual paper map, folded and creased from use, that he carried in a book tucked into the side of his pack. It seemed absurd. Sometimes I went along with it; sometimes my patience wore thin. More often, I judged him silently and teased him behind his back. So what if this guy—who I respected deeply, by the way, a brilliant intellectual—could navigate without Google? Who cared?

What I never stopped to consider, until very recently, is why he cared so much. Understanding the world and how to move through it was part of his identity. Even though he’s young, only just now approaching the big 4-0 like me, he grew up learning to navigate parts of life without the internet. People once turned to him to find their way, and that shaped who he was. Those parts of identity have quietly slipped away for many of us.

Somewhere along the way, many of us stopped asking each other small questions—the kind that used to start conversations, or teach us something about the person answering.

That realization clicked when I was preparing a keynote about AI as a social technology last month. I was searching for personal stories to make the talk come alive, and one memory hit me hard.

I remember lying on my bedroom floor in Pasadena, Newfoundland, at thirteen, the phone cord wrapped around my arm while a friend panicked over algebra. I talked her through a few problems until she said, “Oh, I get it now.” There were dozens of moments like that—test-eve calls, problem sets checked over pizza, and whispered questions that made me feel useful. Somewhere in that rhythm of asking and explaining, math stopped being just a subject and became part of who I was.

That identity carried me through college, when I arrived in Montreal and realized how far behind I was. My small school hadn’t offered advanced courses, and I spent much of my first year struggling to catch up. But when I called friends back home, they said, “Of course you’ll figure it out, you’re so smart.” And I did. I learned to persist because other people believed I could.

Now imagine a student in that same situation today. She probably wouldn’t call a friend. She’d ask ChatGPT, or Gemini or Claude, and the answer would appear instantly and correct. But what shaped me wasn’t access to information, it was the give-and-take that made effort feel shared. What happens to a student’s sense of self when those relationships are replaced by chatbots?

—

Lately I’ve been hearing stories that echo this everywhere I go. Someone recently said, “I used to call my mom whenever I had a gardening question. Now I just use AI—and I realized I hardly call her at all anymore.” It wasn’t said dramatically, just matter-of-fact, which somehow made it sadder.

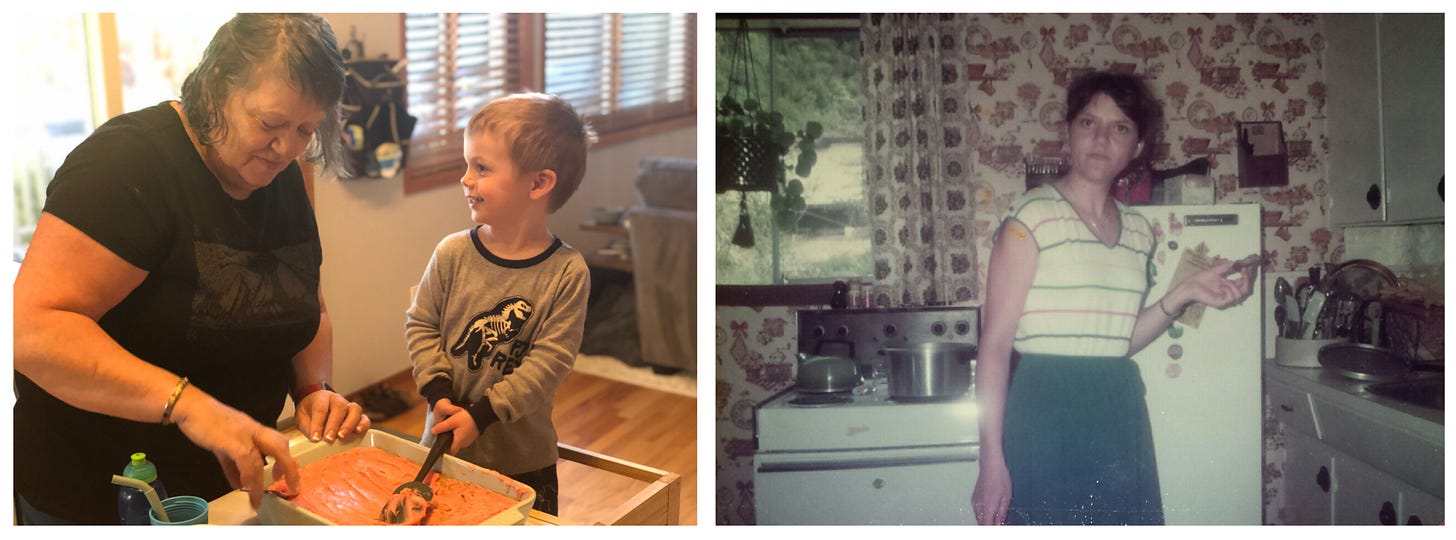

It made me think of my own mom, often in the kitchen with a mixing bowl, always ready with an opinion on butter versus oil or whether a banana’s too far gone for bread. I should really call her.

And a college professor I follow shared something similar. She teaches a few online courses and said her discussion boards used to be full of back-and-forth, with students helping each other troubleshoot, swapping ideas, sharing small jokes. But lately, almost no one posts. When she asked why, a few admitted they just ask ChatGPT now. “It’s faster,” they said. Those were the tiny moments where mentorship happened, partnerships began, and friendships developed.

We’ve gained efficiency, sure. But somewhere in the rush for instant answers, we’ve lost the small talk that used to teach us who we are.

So here’s my challenge to you, and to me. Once a day, before you open ChatGPT, or Google or YouTube, pause. Ask yourself:

What’s my goal in asking this?

Is efficiency the only thing that matters?

Or could this be a moment to learn something deeper, to start a conversation, or to make someone feel needed?

If your question is something highly technical or maybe a little embarrassing, like quantum physics, tax deductions, or that weird lump on your butt, fine, keep it private and ask the machine.

But if it’s something ordinary and human, like fine-tuning a recipe, figuring out how to get your kid to clean their room, or deciding what to plant in the garden, step out into the world and ask an actual person.

The next time I’m standing on a sidewalk, a little turned around, and someone offers to help, I’ll listen. I’ll let them describe the twists and landmarks and maybe even the wrong turns. I’ll put my phone away. Because that woman in Boulder wasn’t just giving directions, she was reminding me what it feels like to belong somewhere, to let someone else guide me for a moment. And if that means getting a little lost, I can live with that.

And for now, I’m signing off. I need to call my dad about cutting the perfect angle for wood. I’m building a secret hideout for my son, and honestly, ChatGPT and YouTube have guided me far enough.

I am 40 years old, writing from Brazil, and I have a university degree, but no postgraduate studies.

Since 2022, I have been have been taking courses at university sporadically. One or two courses per semester, just to refresh my memory and experience the classroom context.

This week we had a presentation where the group had eight people and was supposed to last around 100 minutes. As I am the oldest among the students, I prefer, in these group activities, to wait and see how they organize themselves and only then, eventually, intervene.

Well, a group was created on a messaging app, the conversations were exclusively by text, and the division of topics was done through ChatGPT. Everyone presented – remember, these are in-person classes, not remote – and at no point did I interact with them.

I did my research and enjoyed what I presented as well as the way I presented it, but I can't say how the rest organized themselves. The impression, well, we can make a good guess as to what it was like...

My overall impression aligns with what you said: the subscription to a utility chain whose sole purpose was approval with minimal effort emptied the dialogue.