When Class Size Grows, Do We Prioritize Control or Learning?

What overcrowded classrooms reveal about our tools, our expectations, and what students are really learning.

Have you or someone you know received an email like this recently?

"[Your school], like many schools in the district, will have fewer teachers and student-facing positions in the 25–26 school year. While this is something that is occurring district wide, it will be especially painful at [your school] in the 4th grade. Based on current 3rd grade numbers, having only two 4th grade teachers means 33 kids per class. This is simply too many.

While increased class sizes are limited to a few grades at [your school] next year, letting teachers go is the beginning of a negative feedback loop that will have consequences for all [your school’s] families. Larger class sizes lead some families to leave, which drives down enrollment and funding—triggering further cuts. This pattern is especially concerning for our younger grades: today’s rising 1st and 2nd graders could face the same oversized classes in the years ahead."

I received this a few days ago, and I’m still thinking about it.

And let’s be clear: I live in Boulder County, which is a relatively wealthy, well-resourced, and privileged district. If our school is preparing for 33 kids in one classroom, what does it mean for classrooms across the country?

Class Size Changes What Learning Can Be

I recently spoke with an elementary educator who described how class size dictates pedagogy. In smaller classrooms, you have the space to differentiate, to listen closely, to adapt. But as the number of students grows, the work shifts. There’s less room for nuance and more pressure to maintain order, keep pace, and just get through the day.

This isn’t just anecdotal, it’s backed by research.

Smaller classrooms make it easier to support meaningful learning through constructivist approaches (Piaget, Vygotsky), where students learn by exploring ideas, talking with each other, and making sense of what they’re doing.

In today’s world, that idea grows into connectivist learning (Siemens, 2005), which says learning also happens through our networks—between people, tools, and technology. It’s not just about what you know, but how easily you can find, connect, and build on it.

When classrooms are overcrowded, meaningful learning becomes harder to sustain. Teachers shift from guiding exploration to managing logistics and keeping order. The focus turns to control and coverage, rather than connection and depth.

A 2009 meta-analysis found that students in smaller classes performed significantly better, roughly equivalent to gaining an extra two to three months of learning over the course of a year (Shin & Chung, 2009).

Class size doesn’t just impact instruction, it changes how we perceive behavior

One clear example: the youngest children in a grade are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD. This is part of what is known as the relative age effect.

Younger children in a classroom are ~38% more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than their older classmates.

— Frisira et al., 2024 meta-analysis, European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry

That statistic doesn’t reflect biology, it reflects the system. Younger kids are often less focused, more active, and slower to settle. That’s developmentally normal but in a large, rigid classroom, there’s little room to meet them where they are.

So instead of flexing expectations, we flag the child. When the classroom can’t accommodate difference, we pathologize it.

Wait—Is 33 Unusual?

Not really.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reports that the average U.S. public elementary class size is 19.1 students, and 20.7 students for secondary. But averages can be misleading.

In Boulder Valley, a well-resourced district, classes of 28 to 33 students are common in upper elementary, middle school, and high school. And it’s not just here. Across the country, teachers regularly manage classrooms with 30 or more students, especially in schools facing budget cuts, staff shortages, or enrollment spikes.

Class size also tends to track with wealth. In high-poverty schools, large classes are often compounded by fewer aides and limited support. Meanwhile, private schools average just 14.5 students per class, and elite institutions often cap class sizes at 12 to 16 to maximize individual attention.

It’s like saying the average household owns 1.8 cars. No one actually has exactly 1.8 cars—some have none, some have one, others have three or more. The average hides the spread. Class sizes work the same way: some classrooms have 18 students and extra support; others have 33 and none.

And as those numbers climb, so do the stakes. Teachers have less time for meaningful instruction, fewer opportunities to build relationships, and more pressure to manage logistics and behavior.

Too often, the edtech tools we rely on in those moments don’t restore connection, they just help maintain control.

What the “Hidden Curriculum” Looks Like and Who It’s Designed For

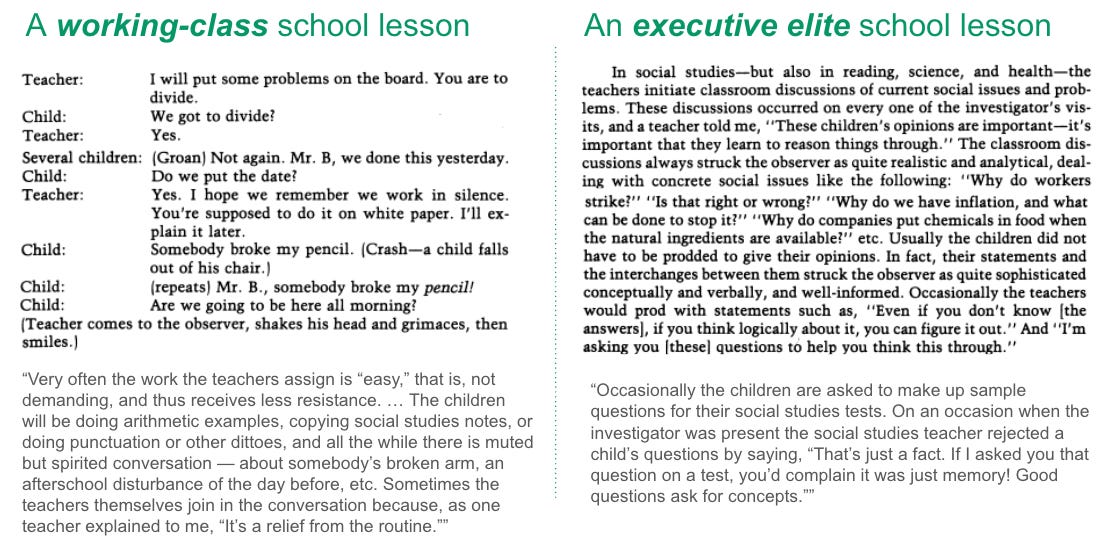

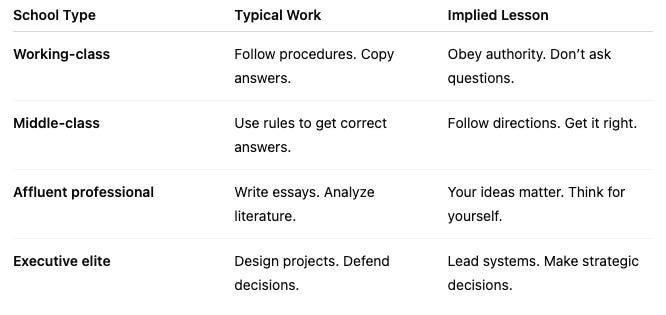

In 1980, education researcher Jean Anyon published “Social Class and the Hidden Curriculum of Work”, an ethnographic study of five schools serving different socioeconomic communities.

What she found was stark: the form of schoolwork and what it prepared students for varied dramatically based on class. It wasn’t just that some kids got more resources, they got a fundamentally different vision of what learning is.

Each group of students was being prepared for a different kind of future and the lessons were embedded not in what was said, but in the structure of the work itself.

When EdTech Optimizes for Clicks, Not Curiosity

Fast-forward to today, and many edtech platforms replicate the very dynamics Anyon observed, just digitized.

The interfaces are polished, but the underlying pedagogy often mirrors a 1980s workbook: complete the task, collect the points, stay quiet. There’s no room for dialogue, curiosity, or student-driven exploration, just efficiency.

These systems aren’t inherently bad. In large classrooms, they can help teachers manage workflow and reinforce basic skills. But when they become the default, when the entire learning experience is reduced to click-through tasks and badge-earning, something bigger gets lost.

And when edtech today follows the same logic, rewarding speed over depth and behavior over thought, we’re not scaling learning: we’re scaling a pedagogy of control.

What If We Designed AI to Disrupt That?

It doesn’t have to be this way.

What if we designed AI to support the kind of teaching that overcrowded classrooms make harder but that every student still deserves?

Imagine a tool built not just to gamify practice but to help students engage with each other’s ideas. A tool that groups students dynamically, surfaces rich prompts, and helps scaffold collaborative thinking so even in a room of 30+, learning can remain social, active, and personal. And imagine it all happening without a screen in front of students.

Instead of measuring progress in speed and clicks, it might help teachers see how student thinking evolves over time. Instead of nudging compliance, it could amplify moments of curiosity, disagreement, or insight and make those moments easier for teachers to spot and support. Rather than replacing the teacher, this kind of AI would put educators firmly in the driver’s seat, surfacing insights that help them do what they do best.

We’re building toward this—intentionally, and in close conversation with the people who know classrooms best: teachers, education leaders, students, learning scientists, and families. We're also learning from AI researchers, designers, and the people who make this work in schools every day.

It’s not ready yet but testing, piloting, and real-world feedback are coming soon!

Because if we’re serious about supporting teachers—and if we believe every student deserves access to meaningful learning, even in a class of 33—we need better tools. And we need to design them differently from the start.

What We Can Do

We can’t shrink every classroom overnight but we can shape what comes next.

Parents: Advocate for increased staffing and ask how your district’s tech supports actual learning, not just compliance.

Educators: Share what works. Push for tools that align with your craft, not just your data reporting.

Builders: Design for real classrooms. Prioritize pedagogy, respect teachers, and center students.

Let’s build something better for our teachers, our classrooms, and the next generation of learners who deserve more than compliance.

> That statistic doesn’t reflect biology, it reflects the system.

(in reference to ADHD prevalence for younger students in the classroom)

Such a powerful statement! I'm excited to see how AI can shift to accommodate different learning styles among larger classes of students. And without a screen!