The Schools We Build Reflect the Future We Believe In

In an age of AI, polarization, and personalization, school may be the last place where we learn to live together

AI is no longer on the sidelines. It is in the classroom now, auto-completing essays, offering instant answers, and pulling focus through glowing screens before students even realize their attention has drifted. Google is rolling out Gemini to schools, including versions built for children under 13. OpenAI has partnered with the country’s largest teacher union to train educators in using ChatGPT. Elon Musk is already imagining Baby Grok, a chatbot designed specifically for kids.

Every major platform seems determined to become the AI your child grows up with, and the race to shape the future of education is already underway.

Everything is shifting fast. And yet when we picture school, the image still feels fixed: desks in rows, a teacher at the front, the bell marking time. It all feels stable, familiar, almost timeless.

But school has never been still.

Each generation remakes school, sometimes quietly and sometimes with force, shaping it to reflect what it values, what it fears, and what kind of future it imagines. The classroom has always served as a kind of mirror, and today that mirror is beginning to crack. In a society that feels increasingly fractured—politically, culturally, spiritually—the question is not just whether we can piece it back together, but whether we can agree on what we want it to reflect.

School has always been a response to the world around it

Imagine you’re born in 1810. You’re walking to a one-room schoolhouse in New England with a slate in hand, and since you’re being educated, you’re probably a white boy. Paper is expensive, so you use chalk to practice your letters. Your teacher is likely the local minister. You memorize Bible verses, copy moral stories, and learn arithmetic. You’re not just preparing for a job; you’re being shaped into someone who is obedient, virtuous, and loyal to the new republic.

By 1910, as America industrialized, cities swelled, factories multiplied, and the school system followed suit; rows of desks were bolted to the floor, bells divided the day into fixed periods, and “efficiency” became the watchword of classroom management. Reformers such as John Dewey, whose 1899 classic The School and Society urged schools to foster curiosity, creativity, and democratic life, tried to counter this trend, yet his progressive vision remained the exception rather than the norm in most public schools.

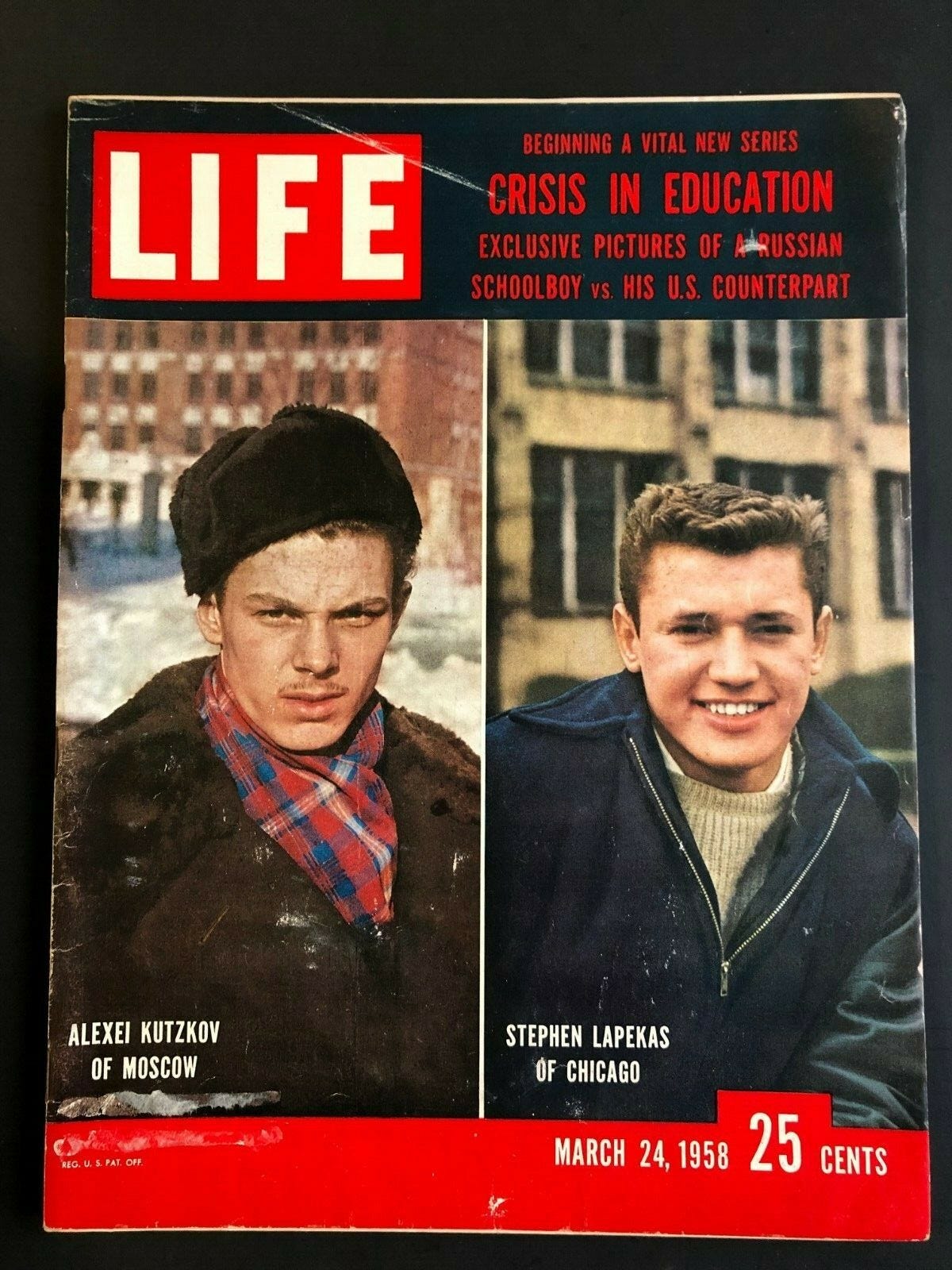

By 1960, algebra becomes geopolitical. The Soviets have launched Sputnik, and lawmakers fear America is falling behind. Congress passes the National Defense Education Act, flooding schools with funding for math, science, and language. Academic performance becomes an act of national security.

At the same time, the civil rights movement reaches the classroom. Brown v. Board has declared segregation unconstitutional, but integration is slow and often violent. Federal programs try to expand access for girls, low-income students, students with disabilities, and English learners but new inequities take root. Tracking, standardized testing, and school funding formulas continue to divide students by race and class.

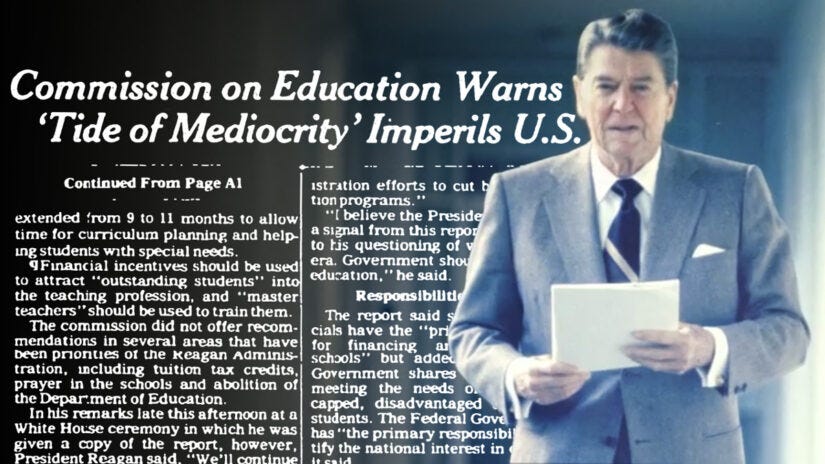

In 1983, A Nation at Risk warned of a rising tide of mediocrity, shifting the purpose of school once again. Commissioned by President Reagan’s education secretary, the report framed academic underperformance as a threat to national survival.

“If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today,” it declared, “we might well have viewed it as an act of war.”

Education was no longer just about democracy or opportunity. It was about economic competitiveness. States adopted standards and tests. In 2001, No Child Left Behind, championed by President George W. Bush and passed with bipartisan support (back when we still had bipartisan support), made it federal law. Schools were ranked by scores, teachers were measured by data, recess and art shrank, and test prep grew.

By the early 2010s, “personalized learning” became Silicon Valley’s education buzzword. Districts launched one-to-one laptop programs, and vendors rolled out adaptive software whose dashboards promised real-time insight on every learner. Yet large field studies found that teachers struggled to stitch together multiple data streams; the RAND Corporation reported that the information was often noisy or incomplete, and educators lacked the time and training to act on it. Journalists visiting “personalized” classrooms saw many students working through identical digital worksheets, their screens replacing paper rather than transforming instruction. Teachers themselves wrote that constant data collection could “drown you” instead of empowering you, because the platforms rarely aligned with what they observed in class.

Then the pandemic hits. Schools shut down and learning moves almost entirely online. Millions of students fall off the radar and the illusion cracks wide open:

School is not just a place for learning. It is where children eat breakfast, see a nurse, talk to a trusted adult, or stay warm through the winter. It is one of the last public institutions that holds kids—physically, emotionally, socially—when everything else begins to fray. When school disappears, it becomes clear just how much we had been asking it to carry.

We are now building the next version of school without agreement on what it’s for

It’s 2025, and students use ChatGPT to write essays, summarize readings, solve math problems, and generate instant feedback. AI explains concepts in seconds, and teachers are left trying to figure out what students actually know. Trust in the learning process is starting to erode. Some schools treat AI as the future; others ban it entirely. Across the country, there’s no clear agreement on what school is meant to prepare students for or even what it means to be prepared.

Yet school has always reflected what we believe the future demands. That’s part of the problem now.

AI is advancing at a pace we’ve never experienced before, and we no longer know what future we’re trying to prepare students for.

Leaders at the forefront of AI development are warning that massive disruption is imminent. OpenAI’s Sam Altman recently predicted that entire categories of jobs will disappear as AI advances. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei projected that half of all entry-level white-collar jobs could be eliminated, with unemployment rising to 10 to 20 percent within five years.

At the same time, President Trump’s new AI Action Plan frames the technology as a race against China, calls for sweeping deregulation to ensure U.S. dominance, and bans what it calls woke AI from federal procurement contracts. The plan pairs that stance with education measures that set new grant priorities for AI literacy, fund teacher-training programs, and direct the Education Department to issue guidance on using federal dollars for AI-powered tutoring and instructional materials but still sidesteps the deeper question of how these tools are reshaping everyday learning and the emotional lives of children.

All the while, public trust in institutions continues to decline, political divisions have deepened, and the idea of a shared reality feels increasingly fragile.

Across nearly every domain—education, climate, health, speech, race, immigration—we are a country divided

We no longer share a civic vocabulary or a common set of trusted sources. Polarization has become structural, and media ecosystems have evolved to reflect and reinforce what people already believe. Social platforms reward provocation over perspective, and the louder the echo, the deeper the divide.

For much of our history, public education offered one of the few shared spaces where Americans came together because we believed in the value of learning to live together. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a place to practice being a public. Today, even that space is under strain.

Classrooms are shifting from shared learning to personalized delivery, where each student gets their own version of the lesson, their own reading, their own AI-generated feedback. Side by side, students can move through the same unit without ever engaging with the same ideas.

There is certainly value in meeting learners where they are. Personalization can close gaps, adapt pacing, and offer support when students need it most. But we can’t over-index and lose the shared foundation that education has long provided. If students never encounter the same questions, wrestle with the same ideas, or hear the perspectives of their peers, we risk losing not just the conversation, but the ability to have one.

We’ve reached a point where disagreement often feels dangerous, and that fear is fracturing relationships—not only between students and systems, but also between families and schools, and between communities and the very concept of public education.

Two diverging paths

If we continue layering AI and personalization onto the existing system without rethinking its purpose, we may find ourselves defaulting into a version of school that optimizes for speed, convenience, and individual completion. Students will absorb content faster than ever. Learning will become more efficient, but less meaningful and more isolated.

But there’s another path.

If we choose to center human strengths, school can become a place where students go deep, not just fast. Where they learn to listen and question, not just complete. Where wonder matters more than performance, and dialogue matters more than answers. Where young people practice the kinds of conversations our society is struggling to hold—about politics, identity, belief, and truth—not to resolve every difference, but to remember how to live together in spite of them.

Importantly, this second path doesn’t mean rejecting AI. It means using it intentionally. AI can absolutely be part of a future that centers humanity but it cannot define the purpose of school.

To get there, we need to have a real conversation about what education is for.

Here’s what I hope comes out of that conversation:

We return to a place where students learn how to engage across difference, hold dialogue, and find common ground.

We choose to value human empathy and connection, and come together to protect children from losing their ability to form real relationships as AI companions grow more emotionally responsive.

We build tools and classrooms that break down, rather than further entrench, echo chambers.

And we do all of this while keeping AI and digital literacy at the center of preparation for the world students are entering.

That doesn’t mean centering AI in the classroom. We can teach digital literacy without pushing kids deeper into chatbot interactions (even those with so-called guardrails) during the limited and precious time they spend at school. Young people will spend plenty of time online. In fact, most already know more about AI than their teachers. So instead of adding more screens to their day, let’s give them space to talk about what matters.

Let’s make school a place where students can wrestle with their values, reflect on what kind of world they want to live in, and learn how to relate to each other.

Thank you for this article. I really agree that we are at a fork in the road between educational paths. It's helpful to focus on the children, because this issue becomes more difficult to address later on, (although not impossible). I wrote this website to help parents think about EdTech. I touch on AI- if we parents can't even get it together to think clearly about our kids on silly apps all day, we will really be on the back foot when it comes to dealing with more and more powerful AI.

https://whycantwesayno.com

https://whycantwesayno.com/what-are-we-not-talking-about/#htoc-16-the-real-digital-divide