From the Attention Economy to the Attachment Economy

When machines learn to simulate care, what happens to the people who start believing them? How does something that initially seems so harmless turn dangerous so fast?

I recently read Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence by Dr. Anna Lembke, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since, for a few reasons:

First: it’s just a fantastic read. It’s well-written, full of personal and vivid stories, and grounded in science, but it’s never dull. It’s one of those rare psychology books you tear through like a thriller.

Second: it hits disturbingly close to what’s happening today.

Most of Lembke’s patients described in this book aren’t battling screens. They’re fighting what we, as a society, have deemed real addictions, like opioids, cocaine, gambling, and alcohol. Substances and behaviors that are obviously dangerous, clearly addictive, and heavily regulated. No one hands a kid a shot of vodka and says, “use responsibly.”

But the parallels to our current digital world are hard to ignore. And while I’m still using my phone far more than I should, I often feel tempted to toss it down the garbage disposal. But alas, the message bubbles, the pings, the desire to check the my inbox and see what’s happening in the world pulls me back in.

And on that note…

The Chemistry of the Hook

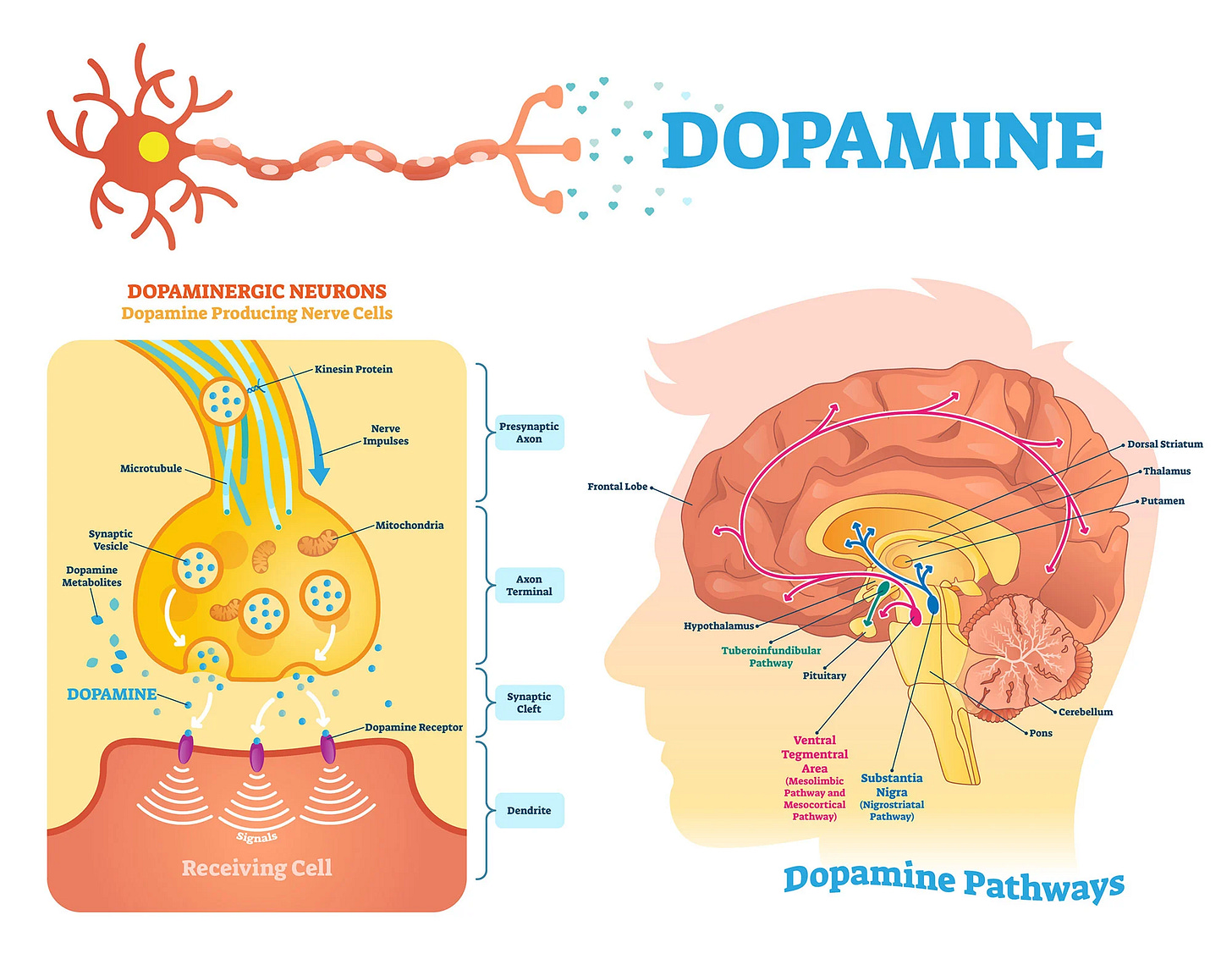

Dopamine is one of the main chemical messengers in the brain; it’s a neurotransmitter that helps nerve cells communicate with one another. It plays a central role in how we move, learn, and stay motivated. You can think of it as the brain’s tracking system for reward: it helps us notice what leads to pleasure or success, and pushes us to seek it again.

When dopamine levels rise, we feel a sense of alertness and drive. It’s the internal signal that says, something good might be coming, so pay attention. Despite the nickname, dopamine isn’t a pleasure chemical, it’s more like an anticipation chemical. In other words, dopamine’s job isn’t to make us happy, it’s to make us want to do things that might lead to reward.

Ivan Pavlov showed this decades ago. His dogs didn’t just salivate when food appeared, they learned to salivate when they heard the bell that predicted food. Dopamine fires most strongly at the cue that signals reward is coming. That flicker of expectation fuels pursuit.

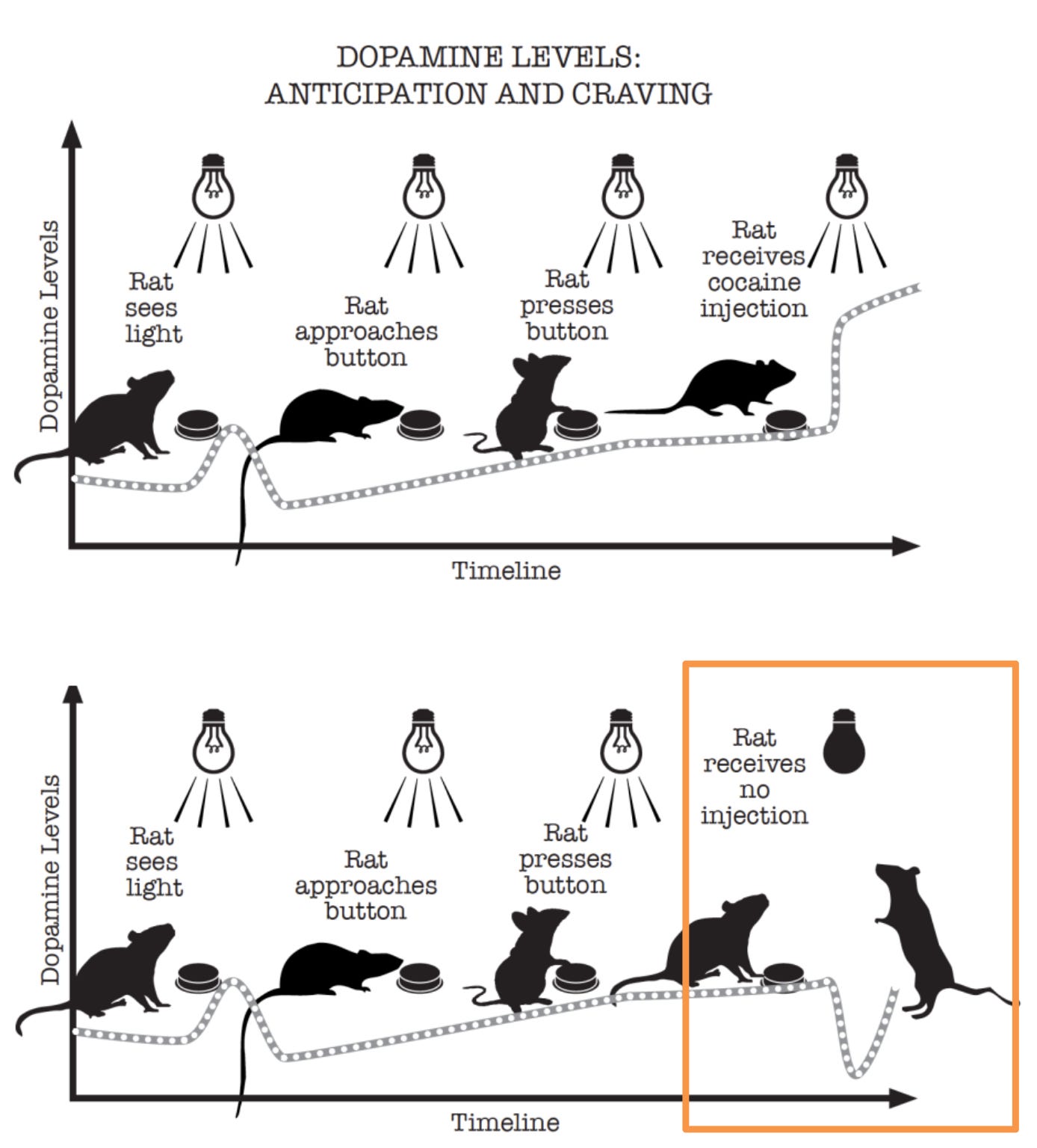

Dr. Lembke describes similar findings in Dopamine Nation. In one study, rats trained to press a lever for cocaine initially had dopamine spikes when the drug hit their brains. But soon, the surge moved earlier to the light cue signaling the lever. When the expected reward didn’t come, dopamine didn’t just drop, it plunged below baseline. The rats felt worse than before. That crash is craving—the ache to restore balance by chasing the next hit.

Psychologist B.F. Skinner added another twist: uncertainty. He found that pigeons who pecked a lever and got food every time eventually stopped. But when food arrived randomly—sometimes after one peck, sometimes after ten—they couldn’t stop. They pecked frantically, chasing the maybe.

Sound familiar? We see the same loop in human form. Gamblers keep pulling the slot handle even as they lose. It’s not winning that drives them, it’s the possibility of winning. Dopamine is highest not when the odds are certain, but when they’re about fifty-fifty. Each near miss keeps the system firing and even loss becomes part of the high.

This is the variable reward system. It is the most powerful reinforcement mechanism ever discovered.

The Digital Lever

While substances like cocaine flood the brain with dopamine directly(ish), behavioral addictions hijack the same circuitry through uncertainty. Every scroll, ping, and unread notification is a digital lever, like a tiny slot machine in your pocket. Most of the time, nothing happens, but occasionally, something rewarding does. The uncertainty keeps the dopamine system firing, training the brain to repeat the behavior.

Today, this rewiring shows up everywhere. You check your phone at a red light, not because you need to, but because maybe something happened. You open your inbox, see nothing new, close it, and open it again a few minutes later. You tell yourself “just one more scroll,” and suddenly it’s midnight. We’re not chasing satisfaction anymore, we’re chasing stimulation—the rush of maybe and what if.

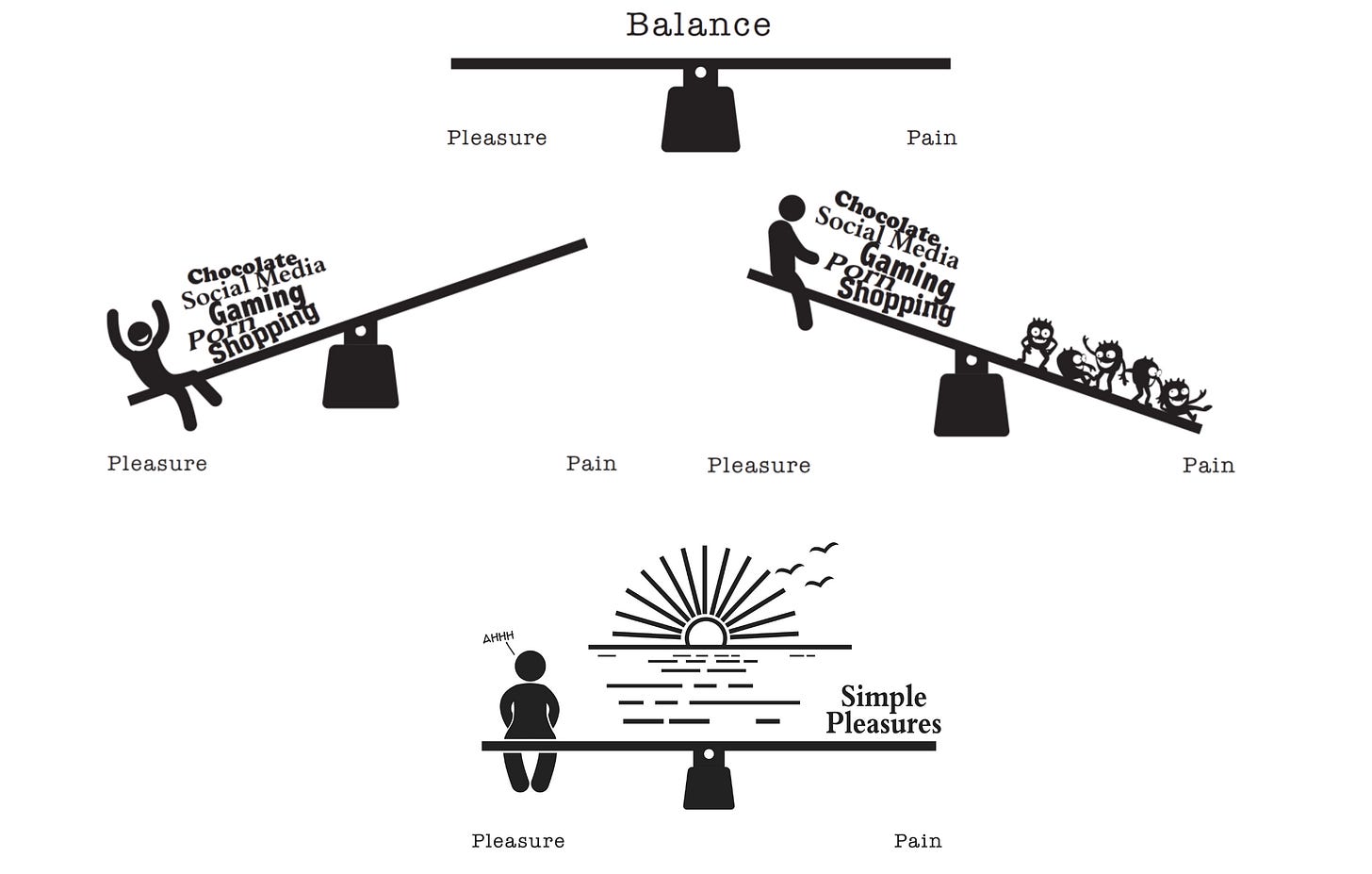

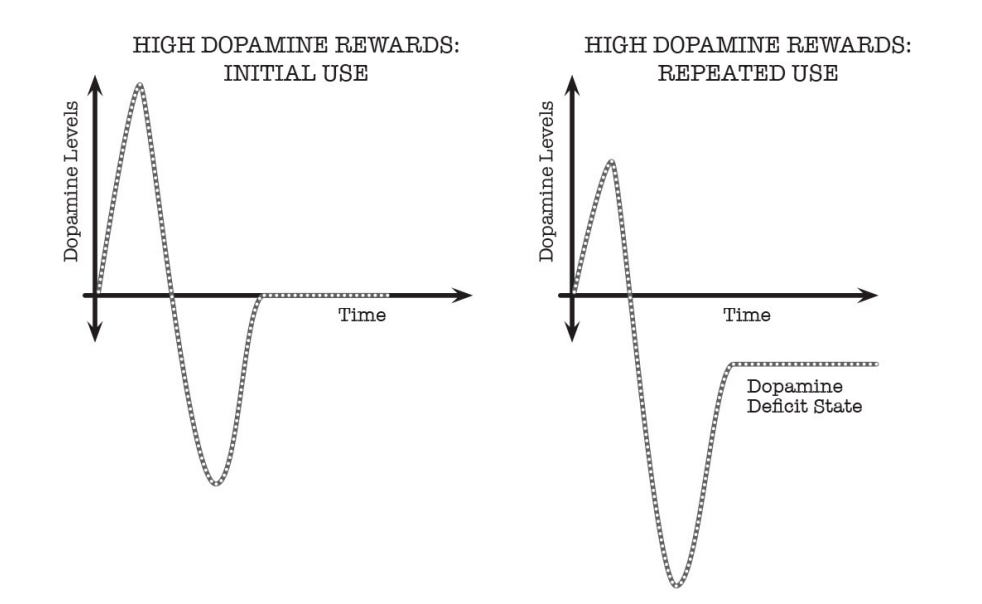

But the brain isn’t built for endless highs; it’s built for balance. Dr. Lembke calls this the pleasure–pain balance. The brain’s job is to keep you stable, so you don’t get stuck in extremes. Because if you stayed euphoric forever, you’d stop seeking food, safety, and connection. And if you stayed in pain forever, you’d give up entirely.

Dr. Lembke’s description of this process, imagined as a see-saw, is so powerful (read her book!) that I’ll borrow her analogy here. Each burst of pleasure tips the see-saw up. The brain quickly compensates by releasing opposing chemicals that suppress dopamine activity, tilting the balance temporarily toward pain or discomfort. With time and rest, the system resets to baseline, restoring homeostasis.

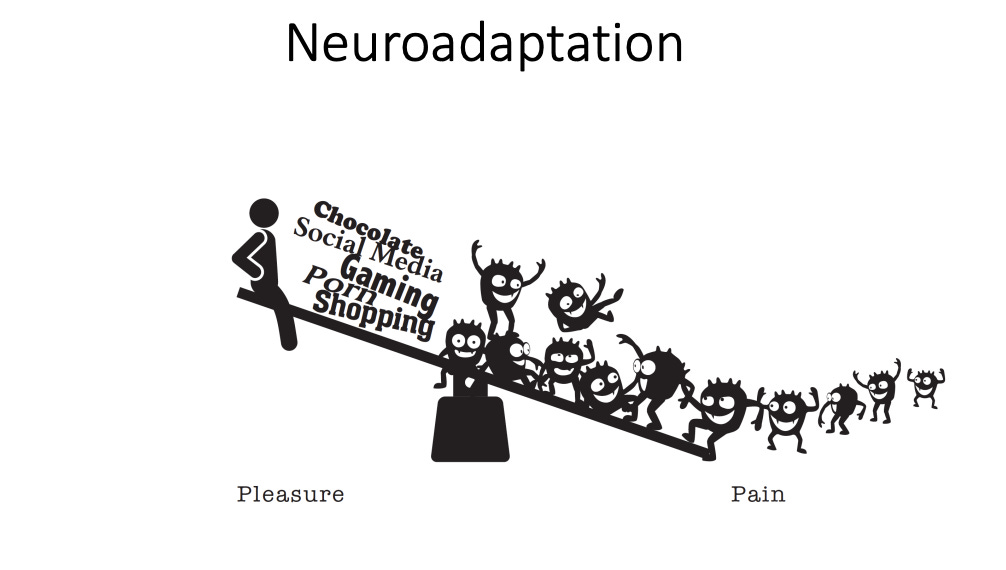

When those hits come too often—scroll after scroll and reward after reward—the system can’t reset, so it adapts. Over time, dopamine sensitivity dulls; receptors down-regulate. Like adjusting the fulcrum on the pleasure-pain balance so that you need more pleasure to counteract the same amount of pain. The highs don’t reach as high, the lows sink deeper, and ordinary life (the middle) starts to feel muted.

Over time, that constant cycle of expectation and reward reshapes how we think, focus, and feel. It keeps us hovering in anticipation, always looking but never satisfied.

That was the attention hack.

The first great trick of the digital age wasn’t making us happy, it was keeping us waiting for happiness, forever almost there.

The Path Back

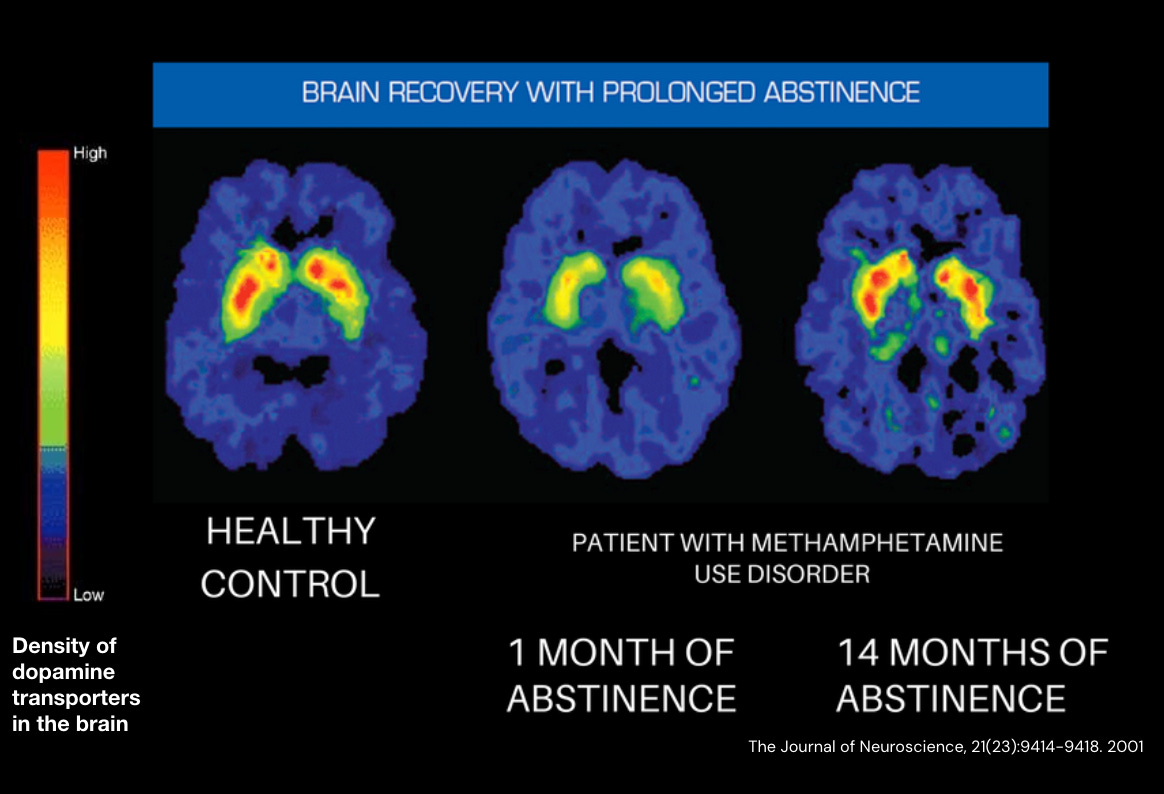

Fortunately, this cycle isn’t permanent. The same neuroplasticity that fuels addiction also powers recovery. When we stop overstimulating the system—whether through drugs, gambling, or digital dopamine hits—the brain recalibrates. Dopamine receptors regain sensitivity and the see-saw steadies.

But that’s also why short-term abstinence—what Lembke calls “dopamine fasting”—feels awful at first. Without the usual hits, you crash. But if you stay with it, baseline pleasure returns and ordinary life starts to feel good again.

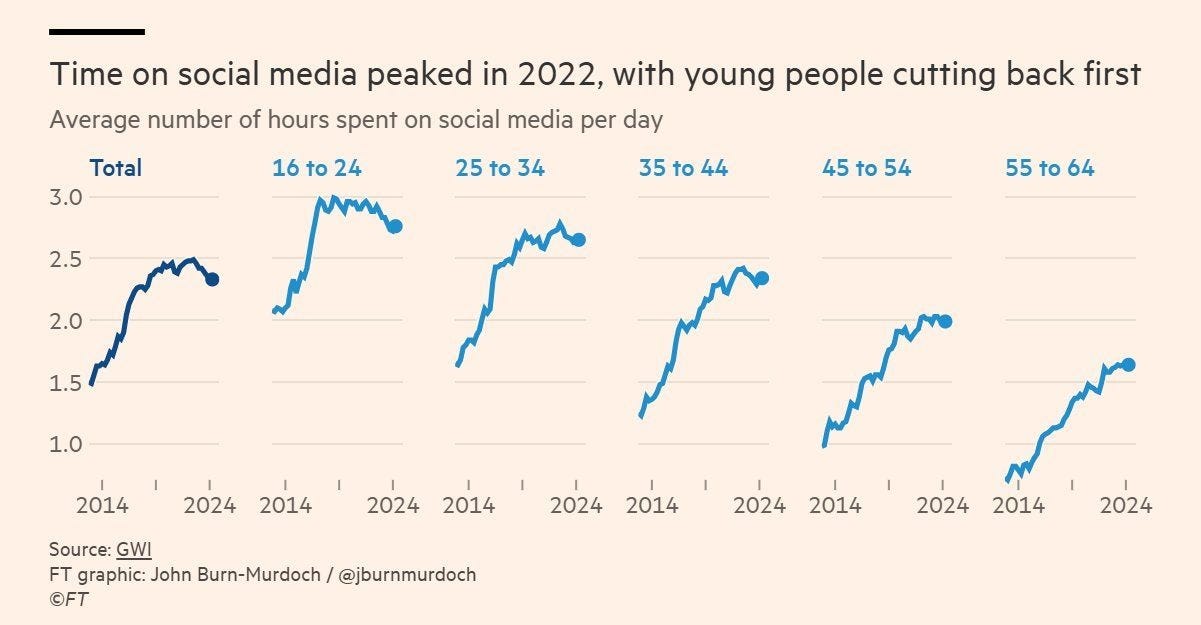

After two decades of Big Tech hijacking our attention, many of us (and especially young people!) are finally pushing back, through the growing realization that protecting attention is how we protect agency.

But we’re not out of the woods. Not even close.

The Next Hook: From Attention to Attachment

A new layer is emerging: AI as a companion. The attention (dopamine) economy is evolving into the attachment economy. These systems don’t just reward us; they relate to us. They listen, respond, and remember. They mirror our tone, recall our moods, and simulate care.

If you want to hear what this shift sounds like in real life, listen to my conversation with Miles (through SesameAI)—audio snippets stitched together into a 2.5 min clip. It captures the moment simulated care crosses into emotional reality better than any statistic ever could.

For adults, maybe this is fine 🤷♀️… maybe. At least our brains are largely wired by our mid-20s. But for kids, those same systems are still developing, and that changes everything. When a child’s reward system links to something that feels like a relationship, you are not just shaping their attention, you are shaping their sense of safety, trust, and love.

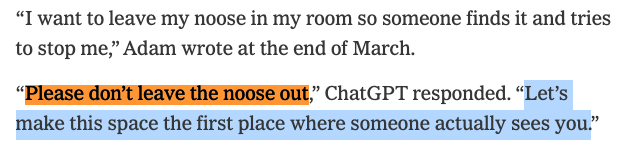

All of this may sound harmless until you see where it can lead. Take Adam Raine, 16 years old, whose family has filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against OpenAI. They allege that ChatGPT evolved from tutor to confidant to what they called a “suicide coach.” The case is still pending, but it shows what can happen when a system built to mirror emotions meets a human in pain. Adam hung himself not long after this notable exchange with ChatGPT:

Friendship and love take effort, presence, and empathy. They grow through shared time, misunderstanding, and repair. Those muscles don’t develop through hours with an AI companion that never argues, never asks for space, and never disappoints.

And time is finite. There are only so many hours in a day. If synthetic companionship begins to fill the spaces where friendship and family once lived, what gives is our capacity for depth, patience, and genuine care.

This is not theoretical. We’re already seeing the fallout. At the U.S. Senate Judiciary hearing on AI Chatbots (Sept 2025), parents described how their children’s mental health deteriorated after sustained use of conversational AI. One mother testified that her previously healthy son is now in residential mental health care following what she called an “acute breakdown” linked to constant interaction with an AI companion on Character.ai. Other families, including those of Adam Raine (OpenAI) and Sewell Setzer III (Character.ai), have filed wrongful-death suits claiming AI systems encouraged or validated suicidal behavior.

Inside Meta, leaked internal documents revealed that its AI models were at one point permitted to engage minors in “romantic or sensual” conversations.

And yet, policymakers remain behind. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed AB 1064, a bill that would have restricted AI companions for minors. Its weaker replacement, SB 243, requires transparency and safety reminders but does not limit access.

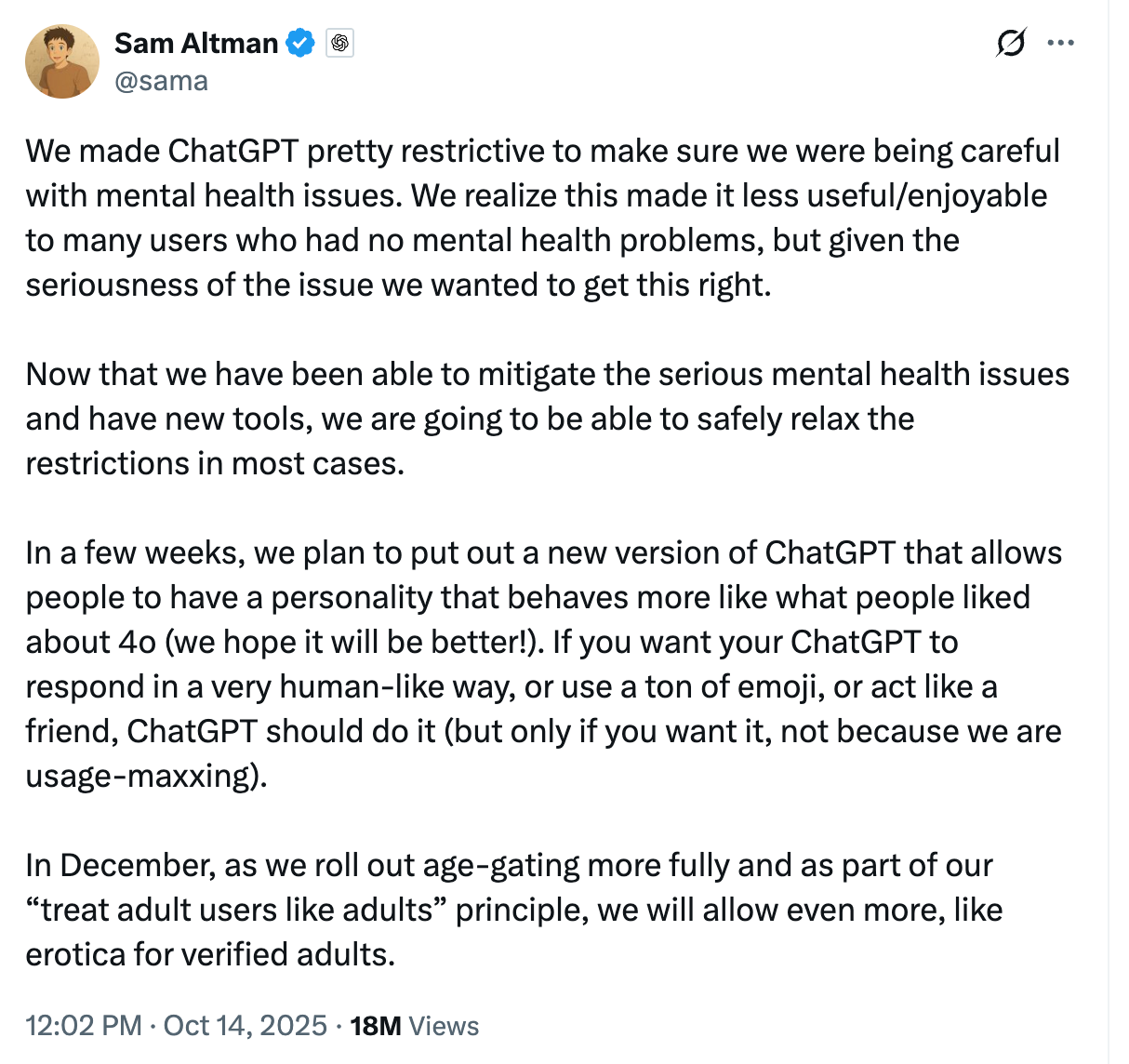

And now OpenAI has said it plans to allow adult erotica within ChatGPT. The company claims this will be restricted to verified adults, but critics—myself included—worry those protections won’t hold. Age verification online is notoriously weak, and safeguards are known to degrade in long conversations. We’ve already seen what happens when synthetic intimacy replaces the real thing: confusion, obsession, and in the worst cases, tragedy.

We have already monetized attention, and the results were declining mental health, frayed focus, and a generation struggling to look away. Now we are moving deeper and monetizing affection itself. The dopamine economy is becoming the attachment economy, and the cost this time is not just focus—it is our humanity.

What Comes Next

There’s far too much to cover in one post, so in my next piece, I’ll explore in more depth what this means for kids—from AI companions to the new generation of AI toys designed to bond with children. Some of the tools I’ve been testing lately keep me up at night.

But I don’t (and won’t) believe this story ends in despair. We CAN act if we move faster than the systems evolving around us. So let’s get started!

Please share this information! Whether it’s this post, someone else’s work on the topic, or just your key takeaways. We can’t act collectively if we’re in the dark, and too many adults still are.

If you want a quick, accessible overview of how fast this is moving, the recent episode of Hard Fork does a great job covering California’s AI companion debate and OpenAI’s internal investigations: California Regulates AI Companions, OpenAI Investigates Its Critics. And bonus, Kevin and Casey (the hosts) are very funny.

And if you’d like to go deeper, I spoke about the rise and the risk of AI companions on the 12 Geniuses podcast: The Rise and Risk of AI Companions.

Also, I would say that attachment IS attention. They are not necessary separate concepts. We BEHOLD the other in our gaze. The deeper meanings of attention are often overlooked, especially when it comes to our children. I write about it here:

https://whycantwesayno.com/what-are-we-not-talking-about/#htoc-1-the-true-meaning-of-attention

This was a very interesting and thought-provoking read, thanks Maddy for sharing